For our second episode, we'll introduce the Jewish calendar -- how the days, months, and years work, why the Jewish holidays move around the secular calendar, and we got to the Jewish year 5,777.

The Jewish holidays move around a lot on our civil calendar. Hanukah bounces all over late November and early December. Passover is in the spring, but could be anytime in April. Sometimes Yom Kippur is in mid-October, sometimes mid-September. Dates are listed both in the English calendar and the Hebrew. Also, it’s the year 5,777. What is going on?!

Relax, it’s not some obscure Jewish ritual that only those “super Jews” know about. The Jewish calendar is based on the lunar cycle rather than the solar cycle,.

Months

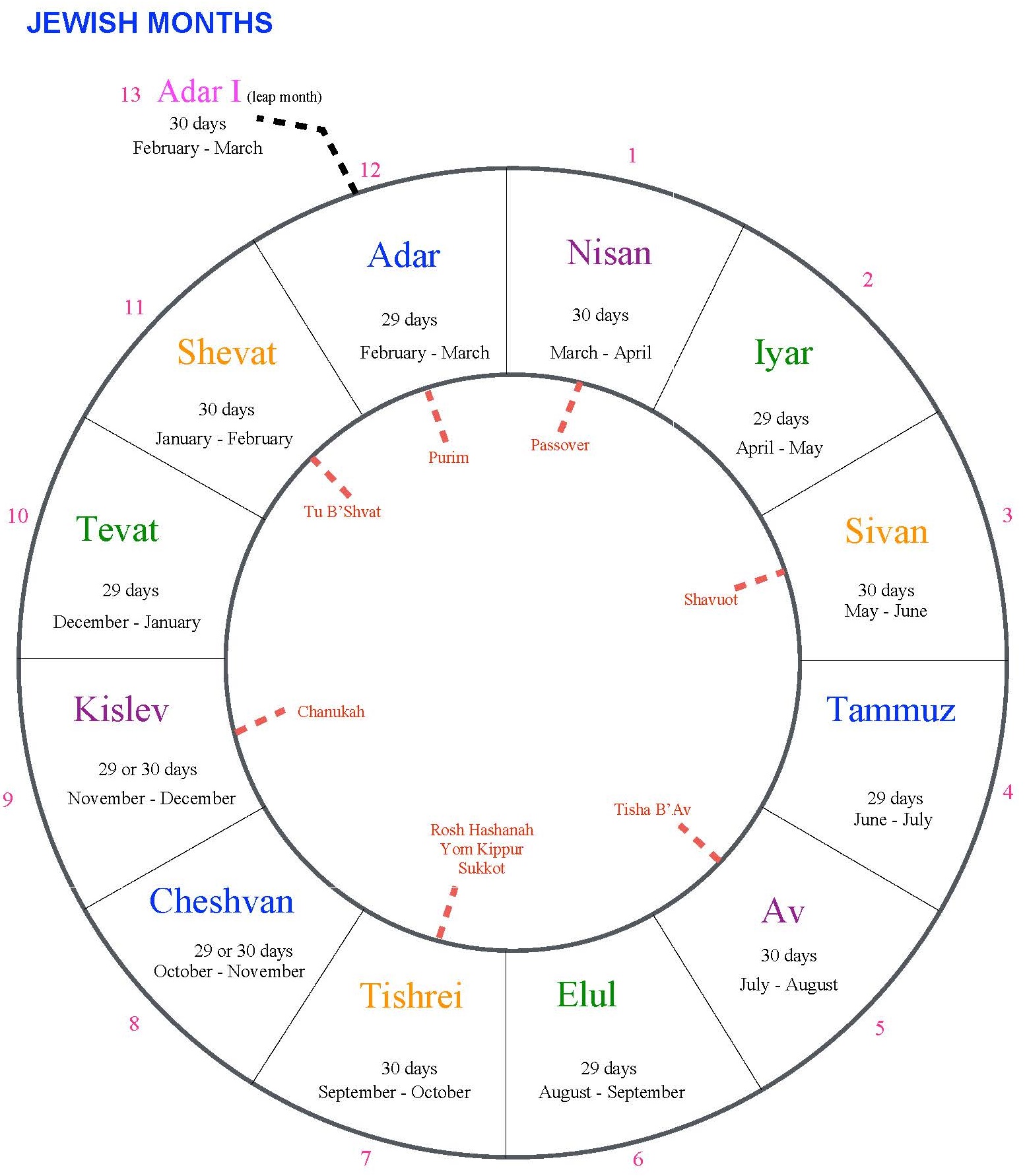

Like the civil calendar, there are 12 Jewish months. The problem is that a 12-month lunar year is 11 days shorter than a solar one; but if we add a 13th month to compensate, it would be 19 days longer. So the Jewish calendar tosses in an entire leap month every now again, and presto! We’re all nice and balanced. But this is why the Jewish holidays drift around the civil calendar.

This extra month is known as shanah me-uberet and literally means a “pregnant year”. By dropping in a pregnant year at various intervals over a 19-year cycle, we sync up with the solar calendar.

In ancient times, the Jews used a system of observation reporting to keep track of the cycle. When I saw from my field that a new moon had appeared, I fired off a dated letter to the Jewish religious authority in Jerusalem, called the Sanhendrin. When the Sanhendrin received letters from two eyewitnesses reporting the same date, they declared that a new moon had risen and thus a new month had begun.

This also explains why some Jewish holidays are one day, and others two. Since the ancient authorities couldn’t be a hundred percent exact with their timing, they would add an extra day to the holiday just to make sure they covered it. This, by the way, is my excuse whenever my boss asks why I took a 3-day weekend.

Nowadays, with our precise calendaring, some Jewish traditions have dropped the extra day. So some Jews only celebrate one day of Rosh HaShanah, while others continue the two-day tradition from ancient times, even though it’s technically not needed.

Years

In the year 160 CE, Rabbi Yossi ben Halafta calculated that Adam, the first human, was created in the year 3760 BCE. It was eventually decided that Year One of Judaism was 3761. To determine the Jewish year, just add 3761 to the civil year, then adjust for Rosh HaShanah. We are now in the year 5,777.

You probably know that the Jewish New Year starts on Rosh HaShanah – the 1st day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei. This date commemorates the anniversary of the date of creation, which is why some people say that Rosh HaShanah is the “birthday of the world.” But there are three other new years’ days throughout the calendar.

In the springtime, around Passover, is the 1st of Nisan, which is observed as the anniversary of the Jews’ escape from slavery in Egypt, and is considered the first month of the year (it’s like January). In the summer, but no longer much observed, is the 1st of Elul, which was essentially the start of the ancient fiscal year – the priests used that date to coordinate the populace paying their annual animal tithe to the Temple. And in the winter we have Tu B’Shvat, the 15th day of the month of Shevat, which is considered the “new year for trees” and thus has heavy agricultural and environmental overtones (the Torah forbids eating fruit from trees less than three years old).

Days

Finally, Jewish holidays begin during the evening of the “night before”, most especially Shabbat, which is observed from Friday night to Saturday night. Why? Because the first chapter of the Book of Genesis says that “it was evening and it was morning, one day.” So evening is actually the first part of the day! Darkness comes before light. Tradition is that evening begins when you can observe three stars in the sky, but the generic “sundown” can also work.

© 2017 Jason Harris